NGC Ancients: Julius Caesar and His Coinage

Posted on 4/12/2016

The numerous coin types of Julius Caesar, minted from 49 B.C. to after his death in 44 B.C., are intriguing historical objects. Caesar was, in fact, the first Roman politician to strike coins with his own portrait at the Rome mint during his lifetime, a generally unacceptable act of political arrogance in Rome.

His earliest known coin portraits, however, were not issued at the principal mint in Rome. Instead, they were struck in 47/6 B.C. at the large city of Nicaea in Bithynia (present day northwestern Turkey), not far from where Caesar had just won a massive victory over the rebellious King Pharnaces II.

By 44 B.C. silver denarii with Caesar’s image were being widely issued in Rome. These coins served as a signal that his individual authority was becoming a threat to the sovereignty of the Republic. Caesar’s coins trace a political career fraught with war and power struggles. But they offer an alternate perspective of Rome’s chaotic transition from the glory days of the Republic and the Augustan Age of the Empire.

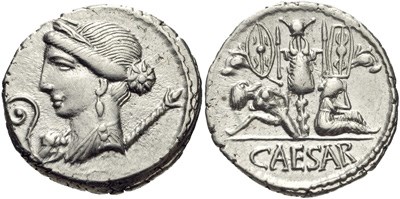

Julius Caesar was born into a prominent Roman family, one that counted the founder of Rome and the goddess Venus as ancestors. A silver denarius of 47 to 46 B.C. (shown above) celebrates Caesar’s illustrious ancestry from the goddess Venus (on the obverse) and the mythological founder Aeneas (on the reverse) carrying his father away from burning Troy. As one version of Rome’s foundation mythology was recorded, Aeneas went on to found Rome and the Gens Julia, the family of Julius Caesar. Julius Caesar ascended the political ladder of Rome, in 60 B.C. becoming a member of the unprecedented alliance known as the First Triumvirate with two powerful Romans: Pompey and Crassus. In their assertion of power, these three men took command of Rome’s provinces. Caesar then became Consul in 59 B.C. and campaigned in Gaul, defeating fierce Gallic tribes and expanding Rome as far as the English Channel.

Caesar’s earliest coins were minted during his military campaigns in the provinces, where he used a mint that presumably traveled with his army. These silver denarii boast of his military success in Gaul, Spain and North Africa, and they feature an array of symbols of victory and influence.

The death of Crassus in 53 B.C. left a significant gap in an already eroding alliance of the Triumvirs. Caesar meanwhile continued to gain military power, and initiated a civil war against the senate and his rival Triumvir Pompey in 49 B.C. During the civil war, Caesar minted coins without the permission of an official Roman moneyer. Without any legitimate source of materials for coinage, he ransacked the state reserves in the basement of the Temple of Saturn. Pliny the Elder recounts that he made off with 15,000 ingots of gold, 30,000 ingots of silver and what may have been the equivalent of 7.5 million silver denarii worth of coinage.

After defeating the Pompeian army at Munda in Spain in 45 B.C., Caesar returned to Rome in triumph. His excessive celebration was cause for alarm to some Romans who were concerned about his motives – especially since his victory was not over a foreign enemy, but fellow Romans.

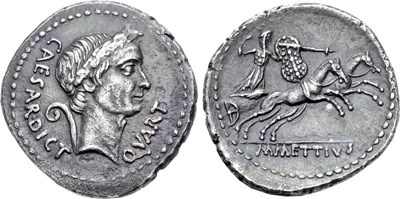

In 44 B.C. Caesar became dictator for a term of 10 years and then ultimately dictator perpetuo (dictator for life). This new title was displayed on silver denarii, which appeared in early 44 B.C. These coins feature the wreathed portrait of Caesar, a token of his established power and authority.

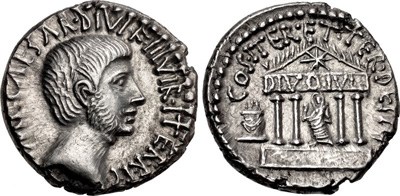

The last coin minted before the fateful day of Caesar’s murder on the Ides (15th) of March depicts Caesar in a priest’s veil as Pontifex Maximus. This title provided Caesar with supreme religious authority in the state, by which he was able to regulate the Roman calendar. In 46 B.C., Caesar used that power to establish the Julian calendar based on a twelve month year. The details of his innovation took hold, and after his murder the month of his birth was renamed July in his honor.

Many sources allege that Caesar’s death was foretold by a number of premonitions, among them a bird augury, a nightmare and an oracle that warned of his death on the Ides of March. With the sense of invincibility of a tyrant, Caesar ignored the signs and was even defiant of them. He even fell ill on the morning of March 15th but remained determined to attend the Senate meeting as scheduled.

In another unfortunate twist of fate on that day, Caesar was delivered a note with explicit warning of the plot but failed to read it. Taking his seat among the senators, who at the time met in the hall of Pompey, Caesar was immediately surrounded by his colleagues-turned-assassins, most notably his protégé Brutus. As the story goes, he received 23 stab wounds and was left to die at the foot of a statue of Pompey, his former adversary.

Caesar’s death marked a turning point in Roman politics. His closest remaining allies – his generals Antony and Lepidus, and his principal heir, his young nephew Octavian – acted quickly to fill the power vacuum. After some initial conflicts, in 43 B.C. they formed what came to be known as the Second Triumvirate, and resolved to defeat Brutus and his so-called “Liberators.”

The Liberators were meanwhile amassing enormous armies in Greece. On the brink of civil war, Brutus disseminated propaganda for his cause in the form of currency. His most famous civil war issues commemorated the assassination of Julius Caesar, not very subtly by depicting daggers flanking a cap of liberty above the legend “EID MAR” (Ides of March). Ironically, Brutus included his own portrait on the obverse, claiming authority in the same brazen manner that not so long before he had found so offensive.

Following the assassination of early 44 B.C., a comet is recorded as having appeared at dusk in the sky over Rome. The Romans believed this phenomenon to be a manifestation of Caesar’s soul transitioning into the afterlife. In 42 B.C. the Second Triumvirate deified Julius Caesar and he was honored with a temple built in the Roman forum. Today the temple is in ruins, but its image is preserved on coins issued by the emperors of Rome. His personal cults were known as the Temple of Divus Julius and the Temple of the Divine Star. The Latin term for comet translates to “long-haired star,” a quality illustrated in the silver coins later issued by Augustus.

Being Caesar’s principal heir, Octavian not only inherited great wealth but also the Julian name, which bestowed him tremendous power and influence. Following in his great-uncle’s footsteps, Octavian took on his enemies with grim determination: he defeated Lepidus in 37 and Antony in 31. In 27, Octavian became Augustus, the first Roman emperor. His reign ushered in the “Golden Age” of Rome, perhaps appropriately represented by this gold aureus below, featuring a portrait of Augustus and his imperial symbol, a sphinx, derived from his signet ring.

Interested in reading more articles on Ancient coins? Click here

Images courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group

Stay Informed

Want news like this delivered to your inbox once a month? Subscribe to the free NGC eNewsletter today!